Riparianism

Check out our global webinar featuring the “Bad River” film series and other related resources here: Reversing Riparianism]

Are you a Riparianist, too?

by Krey Price

June 2017

– a reaction to the June 1, 2017 announcement of the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord –

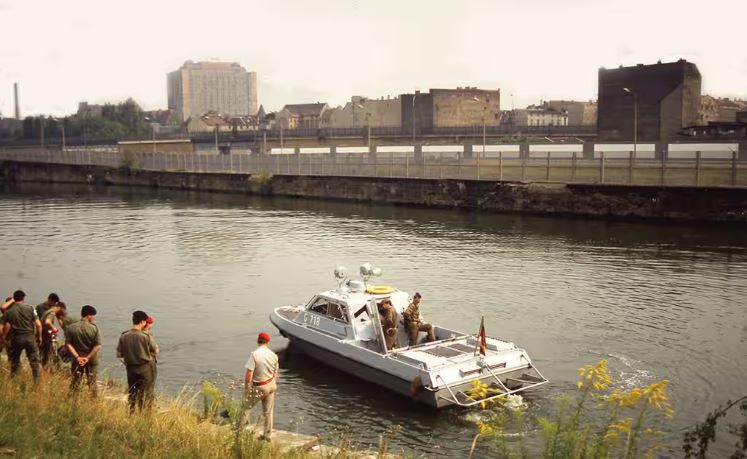

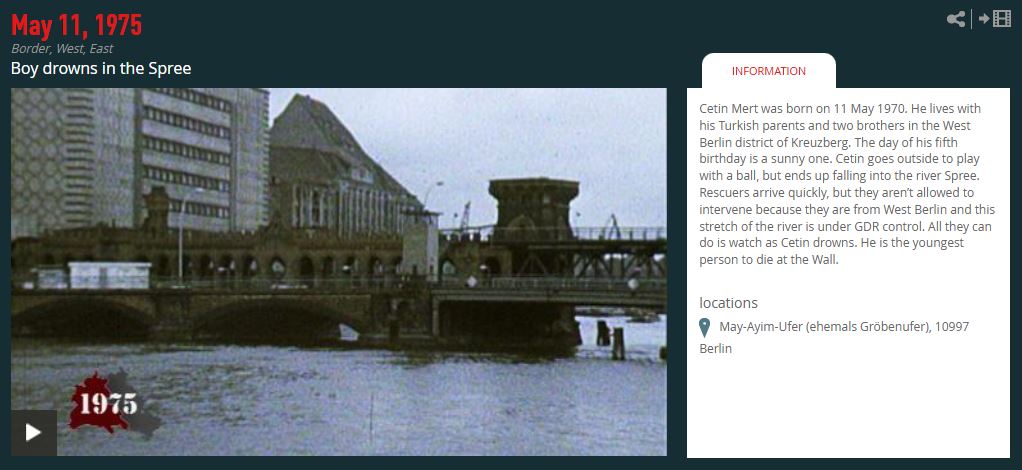

I remember looking across the Spree River at the Berlin Wall when I was a kid. On the bank was a memorial to one of the saddest examples in which a border has ever taken a toll on a river. A young Turkish boy about my age had jumped into the Spree to chase a soccer ball. When the current pulled him away from the river bank, the West German emergency workers who could have rescued him were afraid they would start World War 3 if their rescue boat crossed the imaginary line in the middle of the river. So they watched the little boy drown and filmed their East German counterparts finally coming along to pull out the body. The absurdity of that scene has been burned into my mind since that day, and over the years it has helped to intensity my abhorrence of that wall, the euphoria of watching it crumble, and the knot I get in my stomach when I see walls go back up.

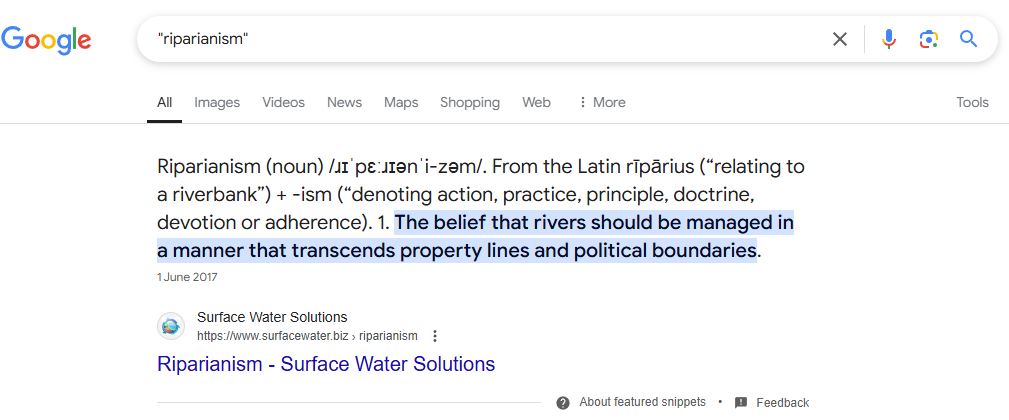

Riparianism (noun) /ɹɪˈpɛːɹɪənˈi-zəm/. From the Latin rīpārius (“relating to a riverbank”) + -ism (“denoting action, practice, principle, doctrine, devotion or adherence). 1. The belief that rivers should be managed in a manner that transcends property lines and political boundaries.

My chosen field of river engineering has two primary goals: protecting us from rivers and protecting rivers from us.

While the goals themselves can be stated quite simply, actually achieving those goals can be incredibly difficult. In ideal situations, both goals can be reached on the same river; at other times the two goals are mutually exclusive, and we have to choose which one to sacrifice. Often we shift the balance too far in one direction or another – sometimes to the point where we make mistakes that have to be undone by our successors.

Balancing act: Too little vs. too much

The desiccated Colorado River Delta (left) and the 2010 floods in Pakistan (right)

Whatever the end result, though, most everyone would agree that both goals are absolutely worthy of pursuit. In the one case we’re saving lives; in the other we’re saving the planet. When the stars align in our favor, we can do both; but when they align against us, we can do neither. Recent headlines mark this lamentable, latter path: Packaged under a banner of profit and security, short-sighted executive orders are building new walls that will ultimately undermine our ability to achieve either one of our alluvial goals.

“Tipping” the scales

(The fact that the bulldozer’s window looks like a letter “T” is mere coincidence…but seems very fitting today!)

I have devoted most of my 20-year career to the pursuit of at least one of those two goals, trying to achieve a balance that I can live with at the end of the day. I sometimes find myself working on both sides of the fence: On one day I might be working on a project that focuses on protecting us from rivers (and by us I mean not just human lives but our assets as well). And the very next day I might find myself working on a different project aimed at protecting rivers from us (and by rivers I mean not just the river itself, but the entire ecosystem that depends on the hydrology of a particular watershed or catchment.)

Sometimes the hydraulic structures I design are intended to keep floods away from people or assets that need protection; in other cases the structures are intended to put floods back where they are needed to sustain an ecosystem. Sometimes I work for developers who want to ensure the safety of the population living behind the levees I design; other times I work for environmental agencies who want me to help bring a riparian zone back to life. Sometimes I help mining companies mimimize flood risk as they extract resources; other times I help salmon swim upstream. Sometimes we have productive partnerships and discussions with mutually agreeable solutions; other times there are heated disagreements and one-sided efforts to tip the balance in one direction or another.

The dichotomy of engineered river restoration: letting environmental flows through while keeping flood flows out

[Yes, this is a restoration project, and yes, this monstrosity is my design…which was later featured in a published conference paper titled “Should engineers be allowed to design restoration projects?”]

In all cases, I aim to simply tell the truth, supported by science. If I don’t know the answer, I’ll quantify my uncertainty. I run model after model, simulating the full range of scenarios my project might encounter, sometimes for periods of 10,000 years or more. Using the best science I can afford under my contract, I scrutinize my models, tweak them, calibrate them, and fine-tune them. And when I’m done, I package it all up and present the results to my clients. Sometimes they like my answers; other times they don’t. But I’ve been doing this long enough and thoroughly enough that my answers are trusted; in the end, my clients use those answers to guide their next move – whether they like the answers or not.

The results don’t lie; the results don’t know how to lie. My software certainly doesn’t know who is at the helm; whether it’s being run by a developer or an environmentalist, the underlying physics engine remains the same. Yes, I could cook the books if I chose to do so, but if I stay unbiased, so will my answers. And if I’ve done my job right, my client will get what they’ve paid for: an objective view of expectations under a particular set of circumstances.

Whether my client is in the business of protecting assets from a river, or protecting a river from the harm that might be caused by those very assets, I simply lay out the risks and the potential consequences. Then the decision-makers, asset owners, and stakeholders step in and decide what risks they can live with, balancing the available funds against the desired outcome. That is my business; it isn’t always easy, but in the end it is rewarding – provided you end up achieving at least one of your goals.

Los Angeles River revitalization: Grand vision with a big price tag

Wherever we can pull it off, we end up with an optimized solution that achieves a reasonable balance between both of our primary goals; those are certainly the projects I find most rewarding. Given funding limitations and technical constraints, in reality some form of compromise between the two ideals is almost always a necessity. But what if we were considering a project that achieved none of our goals – being detrimental to us along with the environment all at the same time? Why on earth would we do it? It ought to get thrown out straight away! But that’s the dismal situation we’re looking at right now. Call it what you will: Neo-nationalism, protectionism, parochialism, territorialism, isolationism – whatever -ism you assign to the current global trends, we are heading down a track that will undermine all of our objectives; we risk losing the battles on both fronts.

The planet’s watersheds and river systems don’t conform neatly to arbitrary lines drawn in a previous century by colonialist ministers. Smoking their cigars in a cabinet room as they carved up maps on an oak desk, their erratic lines often crossed rivers or catchment divides, breaking ecosystem into independently managed pieces. Sometimes rivers were chosen as a fiefdom’s perimeter; whether the lines follow a river or cross a river, the delineations can create substantial threats to river systems as well as to the population and assets all along their banks. Whether or not the political or legal ownership boundaries include actual physical barriers, jurisdictional boundaries and private property lines can cause immense harm and mismanagement of resources that require wider protection and collective responsibility.

The current political climate seems to be prioritizing border security and economic growth over environmental concerns. Tightening up borders may well be a viable or necessary approach worth considering in today’s world. But unfortunately in my game, the same policies that are intended as protective measures end up trickling down to river management policies that interfere with our goals, reducing both our protection from rivers, and the rivers’ protection from us. The example of the little Turkish boy who was left to drown on the Spree River personifies one of those cases in which a border by its mere invisible existence tragically managed to hinder his protection from that river.

Cold War Tragedy: The Spree River and the Berlin Wall

Einstein’s Credo

River practitioners include not just hydraulic modelers and civil designers like me, but also specialists in risk management, floodplain habitat, river morphology, bank stabilization, hydraulic structures, river restoration, wetland ecology, and a number of other disciplines. And whether you’re a miner, a geomorphologist, a fish biologist, a hydrogeologist, or a civil engineer, proper river management brings all parties to the same table, even if there are some underlying differences in opinion and interest.

Some may argue that environmentalists have pushed things too far, for example, while others argue that unhindered development has done the same. Perhaps it’s wishful thinking, but I want to believe that we’re all reasonable people deep down inside…aren’t we? Nobody wants to unleash a flood that takes out a village on its way to nourishing a delta. And nobody wants to jet ski on a river that’s loaded with sewage. The jet skier needs the environmentalist, and the villager needs the engineer. We may push things in one direction or another, but all of us – developers and environmental activists alike – stand to lose as parochialism leads us to protect limited interests at the expense of the entire system – ultimately harming what we sought to protect in the first place.

Albert Einstein didn’t live long enough to have actually stated all of the quotes that are attributed to him on the internet, but well before the dreaded Machtergreifung and the associated roundups, he published his credo – essentially a statement of the beliefs that guided his actions in life – and recorded it with his own voice. In his credo, he stated his opposition to the ambient political climate:

“I am against nationalism, even in the guise of mere patriotism. Privileges based on position and property have always seemed to me unjust and pernicious.”

Now the word pernicious doesn’t appear all that often in modern English, but essentially it just means harmful. I’m not entirely sold on that translation, though; in this case what Einstein actually said in his original German was “verderblich,” which essentially means perishable. It’s an adjective that comes from the infinitive verb verderben, meaning to rot away. Something that has been infected with a dangerous threat that could cause the whole body, vessel, or structure to rot away, for example, would be considered verderblich.

Einstein recognized the signs of the spreading infection; he had previously warned that nationalism was the “measles of mankind” and had expressed his opposition to the “infantile disease.” Having grown up in Germany, I got my own personal view of the aftermath, which has now become entirely entrenched in my psyche. At this point in history, though, Einstein himself was fully unaware of how it would unfold and to what degree it would be set into practice.

In this case, he was merely expressing his disdain for a property-based system of privilege that extended out to a national boundary. The yet-to-be-banned “Deutschlandlied” anthem still being sung while Einstein wrote his credo included direct references to four rivers and straits that formed part of Germany’s borders at the time. In the case of a river system that falls within or along a national boundary, the position of privilege – and the right to use and manage the river’s resources – is claimed based on ownership of a particular piece of the river or its banks. In my eyes, that approach to river management embodies Einstein’s pernicious warnings, whether the boundaries represent national, state, or local borders, or even private property lines: unless we defer to a higher authority, whoever owns a particular piece of the river itself can claim the right to use their piece for their own benefit rather than treating is as part of a system.

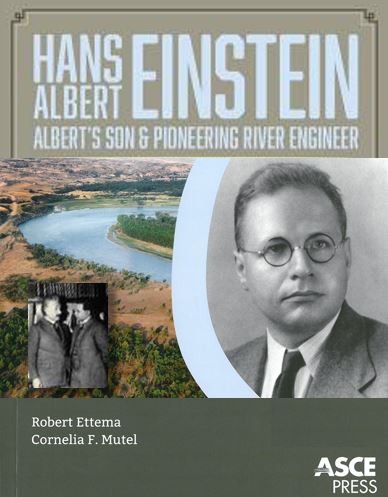

My hydraulics department at UC Berkeley was founded by Hans Albert Einstein, the oldest son of the great physicist. When Hans announced his chosen field of river engineering to his father – so the possibly apocryphal story goes – Dr. Einstein the senior advised his son to choose another field of study. Recognizing that rivers are often chaotic systems with far too many feedback loops for any computing system that Albert could conceive of, he seems to have concluded that introducing a mobile boundary condition into hydraulic models to try to simulate a river’s behavior was simply too difficult. This from the man who brought us relativity!

Hans Albert Einstein: Albert’s son and pioneering river engineer

Although he apparently disregarded his father’s advice and became one of the world’s preeminent river engineers, Hans Albert did not live long enough to see computational power and software innovations advance far enough to support his lofty dreams. We are slowly arriving at that point, however, and we have proven his father wrong in a few rare cases where we have been able to successfully model and predict the morphology of a complex river system. But given the current political climate, we may well take some massive steps backwards and prove him right when it comes to the dangers associated with parochialism.

My engineering ethics require me to stay on the side of science in my professional dealings; now that the science of surface water modeling has finally advanced far enough to be of real use for system-wide river applications, however, it seems ironic that we are facing the unfortunate predicament that the underlying science itself may be ignored or denied.

Pragmatism

I try to be pragmatic in my work. I realize full well, for example, that the “kayaktivists” who protest oil rigs do so in kayaks made of oil-based products. Much as I cringe when tar balls close beaches or rivers are used as conduits for mine tailings, I want to drive a safe car that derives its substance from resources that often couldn’t be extracted and processed without the type of flood protection that I help to provide. But I also want to tell my kids that I did my part in preventing mass extinctions for flood-dependent species – and all others – rather than contributing to their demise. Is it even remotely possible to do both?

If we carve up our watersheds and try to manage them independently, the answer is a resounding “no!” If everyone takes what they can precisely because they can, the system has failed the greater good. In the case of river management, there must be some measure of deference to trans-boundary negotiation and consensus, even when it costs individual landowners and stakeholders something in the short term.

Same team? [photo by AEC]

How many U.S. residents live in the dam failure inundation zones of Canadian dams? Do Americans in the U.S. have the right to expect Canadians to avoid unleashing a flood or passing contaminated mine tailings across the border? In the opposite extreme, how many Mexican residents live in the desiccated floodplains and deltas of rivers that used to flow across the U.S. border and out to the sea? Does Mexico have a right to the historical flows? Under the doctrine that any raindrop that falls on U.S. soil is property of the U.S. government – to be used for its own purpose – Americans have claimed the right to turn off the tap and cut off the supply. Repeat that exercise a thousand times the world over and you will find a heap of defunct systems such as the sand dune formerly known as the Aral Sea – a disaster in mismanagement that has immensely harmed populations, industry, and environment alike.

On the opposite end of the balance between too little and too much water, parochial approaches by individual stakeholders – whether it’s on a national or local scale – can result in larger floods and ultimately a greater investment required from each of those stakeholders to combat future floods. Similar arguments exist in terms of siltation, riverbank erosion, contamination, and other issues. What destroys our coral reefs will also destroy our harbors. And neither benefits in the least from parochial perspectives. We may think we can protect what’s ours by closing borders and building walls, but our ports will be battered and not just the amount of water but the quality of that water will be affected by external threats outside of our control – threats that harm infrastructure and environment equally.

This article is not about pitting companies against environmentalists; this is about uniting those forces against the elements of the rising momentum that threaten both. This is about calling out the “verderblichkeit” of the bling and the temporary high offered by a dope dealer in favor of a system that is sustainable in the long term for companies, individuals, and the planet as a whole. We can wait around until the world either checks itself into rehab or ends up in a ditch, or we can try to avoid either of those outcomes by taking some preventive steps toward sobriety; one way or another, the current addiction can’t possibly last.

Hasenpfeffer Incorporated

The German word “Körper” means body, and you’ll find its relative in the English word corporation. You may read an article or editorial stating that “Company X recognizes…” or “Company Y believes…” or even “Company Z feels…” A company does no such thing. Although by law it is a “body” with some of the same legal rights as an individual, no company is going to feel anything. A company may have an adopted stance that supports or opposes certain actions, but even if an official company representative feels a certain way, that is an individual inclination. And every individual is completely capable of forming their own opinions, regardless of the party line of the company they represent.

That said, we all need to recognize that we cannot rely on companies to lead any opposition to the current trends; it is up to us as individuals. Companies are obliged to draw a wall around their shareholders and act parochially; we must expect them to do so unless there is an incentivized system that makes what is sustainable in the long term profitable in the short term. Until then, each company, and indeed each separate branch of a company, will act in its own best interest. Taken to the extreme, you’ll find that some of the companies that contribute to the coffers of the politicians who deny climate change, for example, are at the same time paying engineers like me to help them prepare for the impacts that they know are coming. Of course, a company knows nothing. It is incapable of knowledge; that is our exclusive right as humans. But those humans who are responsible for determining the acceptable risks for company assets are increasingly deciding that it would be most pragmatic to factor in non-stationarity, gearing up against future fluctuations in weather patterns that differ from those that can be derived from historical records and statistics. By definition, that is climate change!

Now some may argue about what is causing the change or whether our hard-earned cash can have any effect on it. But while we argue, it may be worth noting how many companies are preparing for a change even without the imposition of legislative enforcement. This difference between the public stance and private preparation is not just an opinion; it is traceable with publicly available figures from political action committees and readily accessible engineering assessments published in environmental impact reports. The dichotomy is happening; that is a fact. Whether or not it means anything is up to us to decide.

Typhoon-battered ports worldwide are being upgraded for climate change

Don’t get me wrong – I want businesses to succeed; in fact, we need them to succeed and prosper if there is to be any hope for either our river systems or our lifestyles. If companies are driven out of business, the environment will suffer far worse consequences in the resulting wasteland of unemployment – not to mention that we’ll have to kiss our own lifestyles goodbye. And without the tax revenue from companies and their employees, no government will ever be able to protect us from the next flood – or pay engineers like me to help figure out how to fight it. And I, for one, would like to stay employed.

In an effort to help balance the scales between businesses and the environments in which they operate, there has been a growing trend internationally to adopting the Himalayan tradition of granting legal recognition to rivers, mountains, glaciers, and other natural objects as persons. This may sound a bit outlandish to Western ears, but how many of us work for an inanimate but legally embodied – or incorporated – entity that can no more gasp a breath than the nearest watercourse?

Headlines on a given day may highlight a developer fighting environmentalists or an environmentalist fighting developers; in the end, both sides need science to back up their claims. With science itself under threat of being ignored or denied, though, it is high time to team up and fight the rebuttal of that science. If there are flaws in a given system, let’s fix the flaws. If our models need calibration, let’s invest in the data to calibrate them and then let them stand for themselves. But wholesale dismissals and withdrawals from agreements that are prompted by the exposure of reparable flaws serve only to set us back even further than where we started. As altruistic and cliché as it sounds, the fence needs to be torn down from both sides, allowing us to work together and solve the problems instead of denying them or blaming them on the other side.

Whichever way we happen to swing, most of us feel justifiably pragmatic in our own way. And we feel the right to own what we own and to control what we have control over, without recognizing the collective impacts of millions of independent decision-makers who feel equally justified in basing decisions on their own best interest. At the same time, we tend to call out the abuse of power by political and business leaders who are left holding the cumulative time bomb that we all created with our individual decisions. We nod our heads at the movie lines that link the joint notions of power and responsibility; in this modern era, though, the bond between the two seems to be getting severed. If someone wants less responsibility, that is fine; but they’ll then need to be willing to accept less power and cede any position as a leader. For those who try to maintain power while skirting responsibilities, social activism and the free press will turn the tide against them in the public forum; whether by choice or by force, history will ultimately strip them of their leadership role.

At the same time, we must recognize that those who are powerless are not in a position to take the same level of responsibility. In the world of river management, for example, those without resources cannot be forced to clean up their own mess if they have no capability of actually doing so. Their mess becomes our mess, and those with the resources to act have to initiate the process, fair or not. That is leadership.

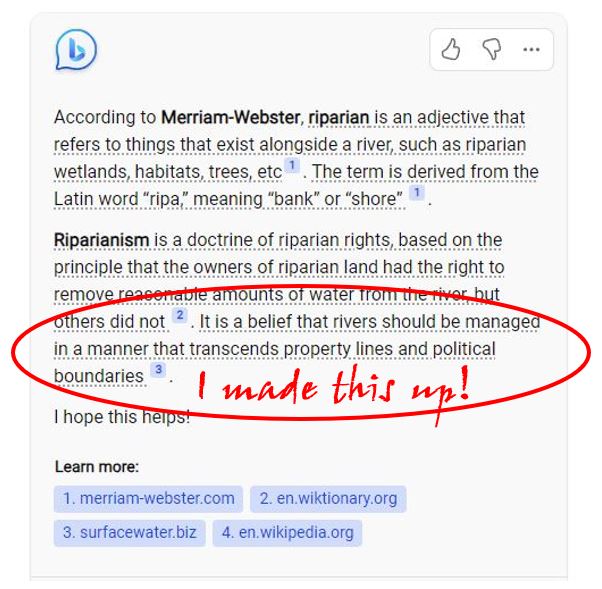

Riparianism Redefined

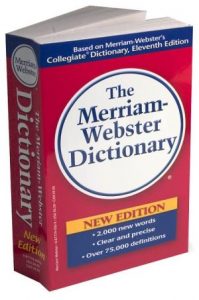

In choosing a title for this article, I wanted to find a single term that reflects my belief that river systems should be managed in a way that transcends property lines as well as national, state, and local political boundaries. I thought riparianism sounded appropriate, but when I looked up the definition, I was surprised to find exactly the opposite connotation. You would need a Ph.D. in U.S. water law to understand the term completely, but anyone with the least familiarity with the subject will recognize that the definition in the header of this article is entirely made up. Yes, it’s rubbish! What riparianism actually refers to is the legal doctrine that those who own the river banks get the right to manage the river; the rest of us, sadly, are out of luck and have no say in the matter.

What? Really?

Yes, according to the legal manuals, under “pure riparianism”, riparian land owners are left to their individual judgments to decide whether, when, and how to use the resource. There is no deference to a higher authority or greater good; there are no collaborative approaches or collective efforts for system-wide solutions. It gives the owners all the say, leaving everyone else with no rights whatsoever to the river’s water or its management. In summary, if you aren’t a riparian land owner, “stuff you!”

Never mind the fact that the river owes its very existence to water drops that fell on everyone else’s property on the way downstream to the river; that’s of no concern. You buy the right to have a voice when you buy the riverside property; if you can’t afford it, you don’t deserve to have a say.

This entitled approach – which sounds a whole lot like the culprit in Einstein’s credo – is highly problematic in the long term. These days, luckily there are many river systems where riparianism has not been the norm; but wherever it has been applied throughout history, river systems have been decimated. When rivers are carved up and each individual piece is managed in a way that provides the greatest short-term benefit to the local jurisdiction or property owner, the entire system suffers. It is not just the alluvial environment alone that suffers, populations and assets are affected as well – assets that are owned by mining companies, oil and gas companies, port authorities, agricultural conglomerates, and a wide range of other interests. In the long term, all are harmed by individualistic river management policies which are sure to increase if the individualistic political climate keeps sweeping the world unhindered.

Victim of “pure riparianism”: the dried up Aral Sea

I reject the traditional principle of riparianism not just in terms of river management but in a thousand other sciences and disciplines as well. The definition itself sounds awfully, woefully familiar in the context of the larger political climate. The world appears to have grown tired of giving to the greater good and getting no immediate, localized benefits in return; so the trend at the moment is every land for itself, with cries of “unfair!” accompanying any move to give back a greater percentage of the resources at their disposal.

I understand the position of those who argue that continual bailouts are not the answer to curing an ailing economy (especially when it’s someone else’s economy!) And I understand why people feel vulnerable and betrayed when innocent lives are taken by someone who entered their border under a humanitarian guise. We want to protect people and assets from threats. I get that. That’s my job too. But the threat I’m looking at comes in a different fashion; my kind of threat arrives in the form of a midnight flood wave that could wipe out an entire city in atomic fashion.

This is only a test: the Superman movie set in 1977

Some of the dams we flippantly fail as hypothetical exercises in our dam breach courses represent real catastrophes that would make the New Orleans disaster pale in comparison. Most dams, levees, and floodwalls around the world were sized under the assumption that future weather trends will match historical weather patterns. Whether it’s the ticking time bomb of Californian levees or Dutch seawalls, a few slight changes in historical weather patterns can quickly expose vulnerabilities. Systems that protect millions are vulnerable to a single breach in an often unpredictable location. Add a bit of parochial mismanagement to the mix, and we have precarious situations like the Mosul Dam, where a breach threatens to wipe out more lives than the conflict that caused the management challenges in the first place!

With that in mind, when I look at the river systems I have worked on over the years, the withdrawal from international agreements and the trend toward parochialism is a disheartening step backwards to say the least. It threatens to undo the results of generations of collaborative investments and lessons learned.

So what about the word riparianism? The word itself may sound like a noble ideology worthy of our adherence, but the real definition is nothing of the sort. I don’t like it; I prefer my alternative definition. What to do?

Well, if I were to heed any counsel from those who are leading the current political charge, here is the message I get: if you don’t like something, just buy it. Acquire it, annex it, appropriate it; then subject it to your will. Isolate it so you can change it into something that suits you and your needs. In essence, treat it riparianistically! Don’t worry about the validity of it all; if it gets enough media exposure, it will become the norm.

So with that in mind, I’ll follow suit here:

I didn’t like the word. So I bought it. And now I’m taking ownership of my $10 purchase and changing it accordingly.

Riparianism.com is now mine. All mine. And I claim the right to do with it whatever I will. If you don’t like it, you should have bought it yourself. Like the tenants who lack riverside property, no ownership means no say!

I fully recognize that there is a previously adopted definition for the word. But ideas are being redefined all the time, and definitions are as malleable as the news these days. And whether or not you like this article or agree with my political rant, by clicking on riparianism.com or Googling the term “riparianism” from now on, you are lending credence to my imaginary definition. Sure it’s fake, but with every click, we’re gradually making it the truth. And if enough people navigate to it, Google will start to spit back my definition instead of the archaic and narcissistic meaning that sprang from water shortages in the American Wild West. And eventually when you look it up, here’s what you’ll find:

“Riparianism: The belief that rivers should be managed in a manner that transcends property lines and political boundaries.”

So there you go. I’ve redefined it. Hopefully my $10 investment was well spent.

Do we even have the right to make up words and definitions? Sure, why not? It happens all the time. After all, kayaktivism became a word thanks to people like this who questioned someone’s definition of the LA River as a “non-navigable waterway”:

That photograph brings me around full circle; after all, it shows the “river” where I first cut my teeth as a freshly graduated river engineer, running DOS-based computer programs to try to simulate the increased flood capacity that concrete floodwalls might provide. Sure, this is river engineering gone wrong in a big way. And perhaps some of the giants on whose shoulders I stand – including Dr. Einstein the Junior himself – may deserve a little roughing up for taking this approach to river management back in the day. It shows us what happens when singular goals – in this case flood conveyance – trump all other goals and no one else is even invited to the table. Even bad examples can serve as good motivation for how we can improve things from here, though, and at least it has made a great film set over the years!

Collectivism: What next?

Don’t get me wrong – I am hopeful. I am full of hope for the future and convinced that driven individuals, collectively, can influence leaders to consider the long-term, system-wide benefits of breaking down barriers and joining forces across political divides. In the meantime, we have mind-boggling amounts of data and computational power at our disposal, along with so many valuable lessons learned from our predecessors. In the face of that knowledge and potential power, if we allow our river systems to become further decimated and allow the riverside populations to be put at risk through the adoption of inane, self-serving policies, we stand to make even worse mistakes than our predecessors – who at least had the excuse of making their own mistakes in ignorance. Not so with us. Future generations will know full well that we should have known better!

Yes, rivers are just one small piece of this insanely complex but delightfully alluring puzzle. If we strain a bit, we might catch a glimpse of the picture on the puzzle box that is only achievable if all of the pieces come together; the dried-up river beds in particular seem to be symbolic of the chaos that we’ll find if we continue with the policies that other driven individuals, collectively, have decided they need from their own countries to feel protected and prosperous. There must be some middle ground in achieving all of our goals; I have to believe that. As a start, I would call on any like-minded associates to help fight the flood of parochial inanity one vote at a time.

If, like me, you don’t have the political clout or funding to influence policies on a national scale, let’s play along with the territorial game that we’ve been thrown into on our own local scale for now. Mine was just a virtual piece of real estate, but if you happen to have a say in how a real piece of land is managed, or have the means to acquire some land in the future, grab it for yourself and redefine it. Protect it by breaking down the barriers instead of building them; devote it to something greater than your own private dock with a fence around it. If a few people are willing to do that, small efforts can serve as models for increasingly larger efforts.

One small parcel being restored in the Colorado Delta

A recent landmark agreement returns less than 1% of the historical flow to the Colorado River Delta. It may seem insignificant, but a few parcels have successfully been turned into restoration sites, and the monitoring results are being used to guide larger and larger efforts. If ownership of waterfront property doesn’t happen to be in your cards, you can still help out with your own form of activism. A number of corporations, for instance, have offered to contribute actual volumes of water purchased and routed to desiccated floodplains in exchange for individual pledges (and they’re free pledges to boot!)

Can we change the course? If we stand idly by and follow ongoing trends, we’ll watch the world put more power and responsibility into the hands of private businesses that have no mandates or incentives to benefit non-shareholders; we can watch the world get chopped up into independently managed states that have to fight symptoms of global issues on their own instead of collectively fighting the causes; we can watch each of those states wring every last drop of short-term revenue from their carved up resources. These are large-scale trends that have built up some growing momentum recently, and we may not be able to slow, stop, and reverse those trends all at once. But let’s not let that stop us from stating our own credo and acting in accordance with it when it comes to the things that do fall under our own realms of expertise and influence! That is how every turnaround in history has begun.

I would hope to see a wave of new riparianism in the form of collective efforts to see past borders and to improve everyone’s standard of living along with the environment. Of course the balance between protecting people and the planet will be teetering for years to come; but what about those forces that represent threats to both? Unless those dualistic threats are combated on both fronts, we all stand to lose. Except river engineers. We river engineers will do just fine, because even steps into the abyss buy us some added job security as we try to help fix the mounting problems that could have been avoided in the first place. All cynicism aside, I’d gladly give up that additional workload in favor of some sensibility and diplomacy in our brave new world.

So there you have it; my little $10 investment marks the beginning of my battle against the threats to both of the primary goals I have adopted as a river engineer: protecting rivers from us, and protecting us from rivers.

How will you fight yours?

Epilogue: Costanzism

That’s it: my first political rant on my company website! If you’re familiar with George Costanza’s “Worlds Collide” theory, you know the danger of mixing your worlds. As the theory goes, the consequence of allowing your personal and professional worlds to overlap can be catastrophic; basically these days it comes down to the notion that your Facebook friends and your LinkedIn contacts should keep a safe distance from each other!

Having spent the last twenty years of my life representing a large corporation as a consultant, I have always tried to avoid mixing politics and any other personal matters with my professional dealings. But now as I go about my business as a “sole trader”, I represent solely myself. And because this sole soul’s professional pursuits are guided primarily by his personal leanings, it seems a bit absurd to keep trying to maintain a clean separation between those worlds. So I’ll go ahead and initiate a collision by sharing this rather lengthy piece about some of the beliefs that steer my personal philosophy and my professional life. I am a neo-riparianist. And this is my credo.

Krey Price

Surface Water Solutions

January 2021 Footnote: I’m feeling more optimistic with the reversal, but let’s hope any problems with the Paris Climate Agreement can be negotiated and fixed in the future rather than being knocked back and forth in the executive order ping pong match!

January 2025 Footnote: Guess I spoke to soon…Feeling disheartened today as I’m afraid we lack the collective willpower to fight this battle or to elect public officials who recognize the threat. Not sure when I’ll change it back, but here is the photo I used for my social media profiles in 2017…and just brought back again for 2025:

In case it needs further explanation, I’m feeling like the old guy at the Hotel Waldesruh, seen at 1:45 and 2:26 here…

Not that it’s any consolation, but I just Googled “riparianism” and it looks like my little investment worked! The made-up redefinition shows up at #1, and Bing AI sticks it right alongside Merriam-Webster’s definition:

Now if we could just start treating our rivers that way!

More info:

- Beau Miles’ Bad River series

- Riparianism global webinar

- Around the world in 100 years

- Change the Course!

- Eight rivers that have run dry

- How the Aral Sea dried up

- Kayaktivism on the LA River

- The Mosul Dam: A Bigger Problem than ISIS?

- The Central Valley Time Bomb

- Billion-dollar Dutch sea walls

- Returning water and life to the Colorado River Delta

- International Riverfoundation and International Riversymposium

- Einstein’s Credo (read by him in German with a written English translation)

- Rivers receiving legal rights as persons

- Reflections on Riparianism

- The Evolution of Riparianism in the United States

- Why I do What I do

- What does a river engineer do? (click on video below for a great summary)

- Cold War tragedy on the Spree River (click on video below for the sad story)