Why I Do What I Do

Costanzism

by Krey Price

November 2016

[click here for the 2021 5-year anniversary update]

If you’re familiar with George Costanza’s “Worlds Collide” theory, you know the danger of mixing your worlds. As the theory goes, the consequence of allowing your personal and professional worlds to overlap can be catastrophic; basically these days it comes down to the notion that your Facebook friends and your LinkedIn contacts should keep a safe distance from each other!

Having spent the last twenty years of my life representing a large corporation as a consultant, I have always tried to avoid mixing family, politics, religion, or any other personal matters into my professional dealings. But now as I go about my business as a “sole trader”, I represent solely myself. And the only stakeholders in my company – really the only ones with a vested interest in my success – are my very own family members.

The road to recovery from Costanzism may be a long and awkward one for me, but because my professional pursuits are guided entirely by my personal experiences, it seems a bit absurd to keep trying to maintain a clean separation between my worlds. So I’ll go ahead and initiate a collision by sharing a rather lengthy story about some of the primary drivers that steer my personal philosophy and my professional life:

Half-hearted

(from Rededication)

Our oldest son Jaedin stopped breathing just after he was born. The memories of that moment are no less vivid and gut-wrenching now than they were on that very long night 18 years ago. He was immediately placed on life support, and the surgeons rushed us to a consultation room to lay out the rather bleak prospects ahead: A congenital heart defect had left Jaedin’s heart with only a single pumping chamber, and he would need a series of very risky open heart operations to survive; his chance of making it through any one of the procedures ahead was essentially a coin toss, but without the operations he stood no chance at all of being with us for more than a few days. The choice was ours to make, but we had to choose right then and there. Hoping we were acting in his best interest, we gambled on the surgical route.

The first operation and ensuing recovery period were painful for us as new parents; saying goodbye to him as they wheeled him off to the operating room for each subsequent surgery became ever more excruciating as we came to know Jaedin’s personality that much better in the meantime. For almost ten years we put life on hold; career ambitions were cast aside as I camped out in my cubicle running hydraulic models, avoiding any change of employment that might risk a loss of insurance coverage or any move that might compromise our immediate proximity and access to the team of surgeons who knew Jaedin best.

Make a Wish

(from Full Circle)

Then one typically rainy winter evening in the Pacific Northwest, we heard a knock on our front door. Standing on our porch were two drenched, but smiling figures in blue T-shirts silkscreened with the shooting star of the Make-a-Wish logo. As it turned out, Jaedin’s cardiologist had nominated him to be granted a wish through the Make-a-Wish Foundation.

“If you could have anything, do anything, or go anywhere you wanted,” they asked him after taking a seat in our living room, “what would you wish for?”

Jaedin looked at his feet, and then glanced shyly upwards, avoiding each pair of eyes that was anticipating his response. Suddenly his own eyes lit up; he had spotted his Titanic model on the mantel.

“I know!” he said excitedly, “I want to go on a ship as big as the Titanic.” Then he hesitated for a moment, looking a bit worried.

“Yes?” prompted one of our guests.

“Only one that doesn’t sink!” Jaedin added resolutely.

Well a few weeks later we discovered that his wish had been granted in the form of a cruise for the entire family! It was quite a treat to leave winter behind for a week-long circle around the Caribbean. Jaedin got VIP treatment at every step; he climbed Mayan ruins, rafted jungle rivers, snorkelled colorful reefs, pet dolphins, and even sat in the captain’s chair at the helm of the world’s largest passenger ship – over 200 feet longer than RMS Titanic herself!

For years we had wanted to play it as safe as we could; we had limited our travels and scaled our dreams to fit the circumstances. But staring at the stars somewhere between Jamaica and Key West, we realised that Jaedin’s own physician had just sent us about as far from a paediatric cardiology unit as we could possibly get. That being the case, who were we to keep him on such a short tether? With his most crucial surgeries out of the way, perhaps we didn’t have to shield him so closely. So when we returned home we started talking about the possibility of changing our venue. Jaedin was all for it, so I began looking for any opportunity that might give him the chance to see as big a slice of the world as possible and to make every single heartbeat count along the way.

(from Jaedin’s Wish)

Winning Numbers

Not long after we returned from the cruise, I heard that my firm was looking to expand into Australia. After talking the implications on Jaedin’s health over with my wife, I decided to put my hand up and offered to be their guinea pig. Having spent most of my career in a technical role as a hydraulic engineer, switching to business development and leading the charge into a new market was an intimidating prospect – especially since our company had no existing contracts or employees in Australia – but they took me up on my overconfident commitment to help build up a business from scratch on the other side of the planet.

As for myself I had only met a single Australian, an environmental consultant named Tanya who had visited the US the previous year in part to take a tour of some river restoration projects I had helped design. I contacted Tanya before our flight and arranged to meet her after our arrival in Melbourne. Other than that I didn’t know a soul down under and wasn’t quite sure where to begin in trying to get our large family established in a foreign country. Our frantic preparations for the overseas move had left us very little time to search for housing online; so as our plane sat on the tarmac at LAX, I fired off one last e-mail from the northern hemisphere: a note to the generic e-mail account of a local church office in Melbourne asking for any assistance they could provide in helping us to find housing.

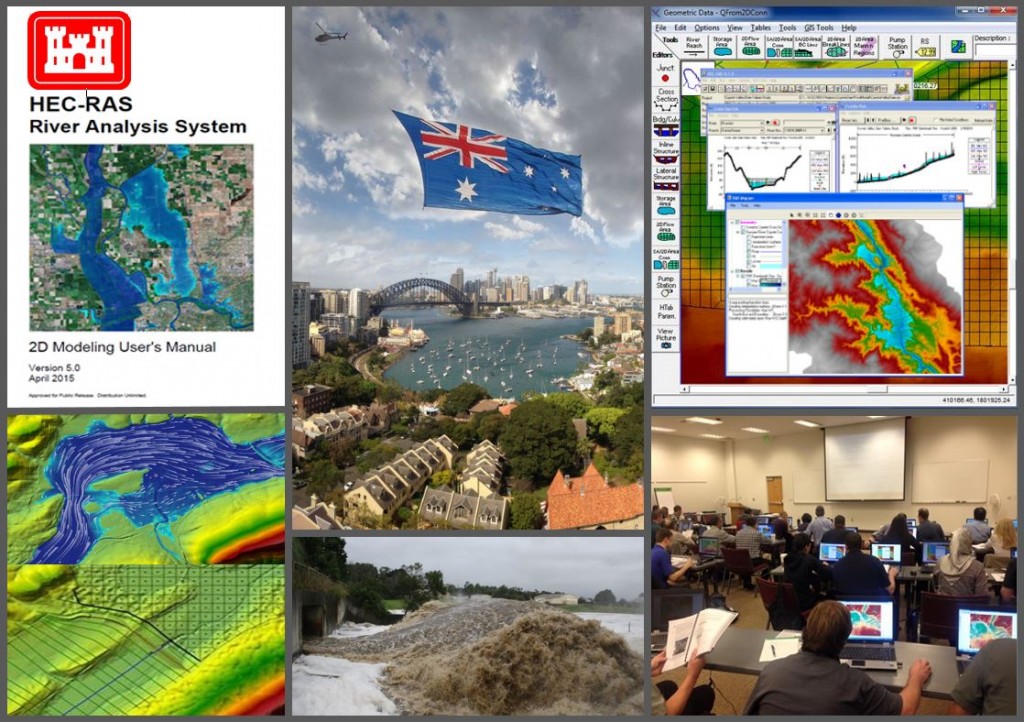

I met with Tanya after we arrived and tried to identify any projects I could help out with. Having managed an inventory of thousands of culverts for a transportation department in the U.S., one thing I could offer was culvert design; as it turned out, she knew some guys at Downer who were trying to replace an ageing trestle for the Great Southern Rail, and they needed a hydraulic design. So I went to the library, downloaded the Australian Rainfall and Runoff manual, and proceeded to work out the local hydrology for the catchment. Using the 100-year old design plans, I built a hydraulic model of the existing trestle along with a proposed replacement design using HEC-RAS, a hydraulic modelling program I had used extensively back in the U.S. I handed the report over to Downer and moved on to chasing other work.

In the meantime, my e-mail about housing had been answered by a fellow named Robert Dudfield. He offered a few tips about rental agencies and recommended some areas we might want to focus on in our search. Over the next few weeks, however, Murphy’s Law hit with a vengeance, and I began to doubt whether this whole Australian adventure was going to work out. On top of the family pressures, my business leads kept hitting dead ends, and I wasn’t sure I was cut out to be in marketing after all.

I ended up boarding a plane to Brisbane in an attempt to try to drum up some work there. When we hit a bit of turbulence, I have to admit my sleep-deprived mind welcomed the thought of just plummeting out of existence and putting an end to the stress right then and there. As I sat on the plane doubting myself, though, I thought of my family and the fact that they were all counting on me to make it work. Not knowing how much time we had left with Jaedin, I really didn’t want to go home without having tried my absolute hardest. Just before landing in Brisbane, I finally got up the nerve to practice my marketing skills on the guy in a suit sitting next to me. I struck up a conversation with him and handed him one of my freshly printed business cards; he looked at it and paused for a while, seeming a bit confused.

“Well that was a bit awkward,” I thought to myself, “Maybe being a business development guy just isn’t in my cards.”

He was still staring at my card. Finally he spoke up. “Oh yes, now I remember why I recognise your name,” he said, “You sent me an e-mail when you were just arriving in Australia.”

I was totally stunned.

“I’m Robert Dudfield,” he said.

My first reaction was to look around for a hidden camera somewhere. This certainly couldn’t just be a chance encounter…or could it? As it turned out, the Hail Mary pass that I had sent out from the other side of the world had somehow ended up in the hands of this particular guy who just so happened to be sitting in this particular seat right next to me on this particular plane!

Given the tiny percentage of people we ever get to know in this life, I could probably live in airports and take flights every day for the rest of my life…and chances are I would never just randomly sit by anyone I knew. With the four million strangers in the Melbourne area who might have stepped onto a plane that day, the odds of sitting next to Robert made me feel a bit like a lottery winner. Our brief conversation that morning didn’t necessarily solve any of my problems; armed with that experience, though, I found some personal meaning in the encounter, which allowed me to go about my business with more confidence, enthusiasm, and determination than before.

Culvert in a Haystack

I ended up giving a presentation at the International Riversymposium in Brisbane; a catchment management association representative named Adrian heard the presentation and asked me afterwards if I would be a keynote speaker at a floodplain management conference he was hosting in Victoria. Looking for any leads I could possibly land, of course I obliged.

When I finally spoke at the flood conference – after a whole lot of additional dead ends – Adrian introduced me to one of the community planners in attendance named Duncan, who proceeded to tell me about some of the stormwater issues being faced by the communities he was working with. Duncan asked if I’d serve as a consultant on a project to identify drainage solutions for some of these communities. Again, of course I was very happy to oblige.

Duncan and I ended up driving several hours away to a rural town called Dimboola to interview some locals about their flooding issues and have a look around. He explained that their stormwater issues were complicated by a railway that ran right through the middle of town. One drainage crossing in particular was serving as a bottleneck and would need to be upgraded. As we walked along the railway and arrived at the crossing, he seemed a bit surprised to find a brand new structure.

“Well I guess they’ve replaced it in the meantime,” he said.

The culvert looked vaguely familiar to me, but I couldn’t figure out why.

“Oh that’s why I recognise this culvert,” I finally told Duncan after putting the pieces together in my head, “I designed it!” Sure enough, it was the rail culvert I had designed for Downer with Tanya’s connections.

So my first two jobs in Australia just happened to be centred around the very same little culvert, and the two jobs landed in my lap through two entirely different routes. Given the 100,000 culverts in Victoria alone, what is the chance that I’d find something familiar hundreds of kilometres from anywhere I had ever been before? If you could shrink each of those culverts down to the size of a stalk of straw and pile them together, you’d certainly have a massive haystack – and I was staring right at the elusive needle! Similar to the way I had felt on the plane to Brisbane, in this case I found myself looking up at the sky, wondering why things had come around full circle for me yet again. And again, there was no accompanying windfall; I still had to work my ass off every day to compete for every new contract and justify the company investment of keeping an expat on the books. But culverts are kind of my thing, after all; so as before, I took some personal meaning from the improbable coincidence.

Refugees

After two years in Melbourne, I ended up riding the mining boom out to Western Australia and found myself with more work than I possibly could have imagined. It was very rewarding to finally see all of the initial efforts pay off; fast forwarding another four years, though, the mining boom went bust, and my company decided it was time for my temporary assignment to come to an end. When I broke the news to my family that it was time to go home, they were devastated. Jaedin, in particular, was heartbroken; he told us that he really wanted to stay and finish high school here in Australia.

So I decided to at least test the waters and see if there was any possible way we could stay. Perhaps the contact list I had spent so much effort in compiling over the previous years might come in handy; I dug it out and fired off over 600 e-mails with my resume to see if anyone would bite. I got a lot of friendly replies back, but not a single lead for a job.

“Too bad you’re on a 457 visa,” I heard time and again.

Our ability to legally reside in Australia was tied to my specific position. No job, no visa. And my temporary visa stipulated – along with a number of other onerous terms – that any employer wishing to take over the sponsorship of my visa would have to demonstrate that there were no qualified Australians who could do my job. Plus I had to keep doing exactly what I said I’d be doing under the original sponsorship application. But the scariest proposition to any potential employer was the obligation to ship our entire family of eight back to the U.S. at their expense should the circumstances change. With hundreds of out-of-work, Australian consultants shopping their cvs around to the same employers, I didn’t stand a chance.

In the middle of these failed efforts to find a job, we started noticing some swelling in Jaedin’s legs and chest. We took him to see a cardiologist and got the devastating news that he had been diagnosed with a protein-losing blood condition called PLE; with his heart slowly failing, he was now facing a second incurable condition that would likely make any further surgeries too risky to undertake.

Perhaps it was best for us to go back home after all. We sat down with Jaedin and explained the situation. Knowing that his time may be short, we asked him whether he would want to return to the U.S. or stay in Australia if he had the choice. He thought about it for a while, headed outside, and wrote a letter listing all of the things he loved – and would miss – about Australia if he had to leave. He taped a gum nut from one of the towering gum trees in our yard to the letter and handed it to me without a word. His letter brought me to tears. Had I really done all I could to fulfil his wish to stay in Australia? My wife and I talked it over and decided we would leave it to fate – and put the immigration department to the test.

With a resignation letter to my company of almost twenty years – my only employer since my university days – we dove blindly off the cliff. The resignation automatically cut off our expatriate benefits, severing every lifeline we had to our former home. We cashed in our entire retirement superfund, and I decided I would just stay put and keep sending out resumes until there was nothing left in the bank and immigration officers showed up at our doorstep, cuffed us, and dragged us to the airport against our will.

Well despite my newfound resolve, I was having no better luck with my second round of the job hunt. One day as I was complaining to a friend named Michael about the dire state of the WA mining industry, he said, “I heard Peter Meurs, an Executive Director over at Fortescue, speak the other day, and he seems to see the light at the end of the tunnel. Why don’t you give him a ring?”

“Sure,” I said, “what’s his number?”

I was totally joking, but sure enough, Michael texted me Peter’s personal e-mail address and phone number. I carefully crafted an e-mail to Peter and was even more surprised to hear back with an offer for an interview with him and some of his colleagues at Fortescue. The interview went well, but it turned out that due to my visa status they couldn’t help me either. I felt a bit let down, but at the end of the interview I was told that one of their contractors had a hydraulic modeller who was heading back home to New Zealand, leaving some unfinished HEC-RAS work that had to be delivered. After so many dead ends, I had nearly given up hope that anyone would be crazy enough to sponsor my visa, but I gave the crew at MWH a call anyway.

Their first question: “Do you know HEC-RAS?”

Although I was familiar with older versions of HEC-RAS, it wasn’t a commonly accepted program in Australia, so I was a bit out of practice. But my marketing experience got the better of me and I confidently answered, “Yes I do!”

And sure enough, my 601st resume ended up landing me an interview, a job offer, and ultimately a sponsored visa that bought me just enough time to get the immigration department off my case until I could submit a permanent residency application for the whole family.

I still wasn’t sure it would be possible, though; we had been told that Jaedin’s health problems would surely knock us out of the running for permanent residency. So when we finally received our grant notice – that said “Indefinite” under the stay period and “Nil” under the conditions – to me it bordered on miraculous.

Academia

With my new job I could really picture what some of my ancestors must have felt when they gave up their careers and their lives in their native countries to start from scratch as immigrants in a new land. In the beginning it was a tough swallow to switch from an executive path back to a technical role in hydraulic modelling. But even though it set my career back about twenty years, in the end it also reduced my stress level and allowed me to explore another direction for my work – one that I now thoroughly enjoy as a bona fide Australian citizen. Here’s how that chapter began:

Shortly after our permanent residency application was approved, I ran into Michael again at a dinner party.

“Glad you managed to find a job so you can stay here,” he said. “Can I introduce you to Richard? He’s an engineer too.”

I shook hands with his new friend Richard, a Chinese student who was looking for an internship in order to graduate with his mining degree.

“Got anything he can work on?” Michael asked.

I shook my head. Times were still tough in the mining sector. With pay cuts, reduced hours, and layoffs on the horizon across the board, everyone’s job was on the line – including my own – and nobody at MWH was about to take on a new hire.

As I was searching for the words to let him down tactfully, though, Richard added, “I work for free!”

Well that little detail certainly got my attention; as a matter of fact, one of my clients had just asked me the previous day if I could help out with a modelling project – but one that he had no funds to pay for.

“Sure, we’ll put him to work,” I said.

I turned Richard loose on the new beta version of HEC-RAS, which I hadn’t mastered yet in its current form. Over the next few months he did a phenomenal job with some benchmarking studies; I ended up presenting his results in client workshops, Engineers Australia seminars, and training sessions around Australia that resulted in a great deal of interest. Just by word of mouth, a couple of brown-bag sessions at Melbourne Water and Brisbane City Council attracted almost 100 attendees.

Given my recent unemployment, I had been looking at some adjunct teaching opportunities as added security against future layoffs and pressures to work reduced hours. Lacking the requisite doctorate degree, though, I didn’t get anywhere with the idea. The interest levels in the new version of HEC-RAS, however, got me thinking about alternative teaching options; I started collecting expressions of interest for software training and got an overwhelming response.

I wasn’t sure where to start with an official training course, so I did a quick Google search to find out who might be offering HEC-RAS training internationally. When I ran across Chris Goodell, the author of a popular HEC-RAS blog, I called him up and said, “How would you like to come to Australia?”

“Count me in!” he said.

Reflection

Well that answer ended up being the beginning of Surface Water Solutions, my new software training and consulting business. I was certainly glad to hear the positive response, but somehow I already knew it was going to work out from the time I first jumped off that cliff. Call it faith, or trust in the universe, or the naïve insanity with which a bird first free-falls out of its nest. Whatever you call it, that feeling is a bit hard to explain – to me it felt a bit like deja vu.

How does a migrating bird or butterfly know it’s on the right path out over the open sea? I certainly can’t explain the homing beacons they follow across vast distances, but there is some combination of instinct and other completely natural but inexplicable forces driving those creatures home. In a similar way, sometimes in life, we seem to pass recognisable landmarks that we’ve never seen before. In my case over the last few years, some of these landmarks have included a chance conversation on a plane, a culvert in the middle of nowhere, a visa approval letter, and now a teaching partnership for a hydraulic modelling course.

Now a lottery winner may think it’s a miracle to have won a particular draw, but to the rest of the players it was just plain chance; I get that. But somehow each of these seemingly mundane events combined a tangible familiarity along with such a remotely small probability of occurrence that I genuinely struggle to see how they could just have occurred randomly. Some may call them dumb luck; others call them miracles. If these crazy coincidences had only happened to me once or twice, mere luck might be the only factor involved. But I’ve had hundreds of these experiences, and I could keep telling similar stories all day long. At some point if you watch a lottery winner keep winning over and over again – to the point where the odds of a particular series of wins would put the probable recurrence well past the end of time – you might begin to suspect that the system is rigged. And I guess that’s where I’ve landed for the moment.

At the same time that I resigned from the corporate world and struck out on my own career path, I also resigned from the religion of my youth and struck out on my own philosophical path. For me personally, that latter journey was much more substantial than a mere job choice could ever be. The journey of ethereal reprogramming has taken years, and I’ve now reached a point where I consider myself completely agnostic in terms of anything metaphysical; but like the stage light that drops onto Truman’s street, some of these experiences still leave me wondering what the unknowable is all about.

By no means has this path ever been easy – none of these epiphanies simply removed problems without requiring a whole lot of effort on my part; but every time I bother to look, I keep seeing signs of the rigging. I don’t claim to have all of the answers – or really any answers at all – and I definitely don’t claim to possess any inclination of whether there is such a thing as divine intervention…and if so, why the control room would choose to intervene in these particular events that ended up falling into place for me. But knowing that each of these landmarks just happened to appear after desperate pleas to the universe, I do believe that I am where I am supposed to be. And that I am somehow meant to be doing what I am doing.

Above all, I feel a measure of guidance that – so long as I put in my best effort – I expect to continue, come what may. Armed with these experiences, I fully expect more landmarks and road signs – in whatever form they may come – to keep pointing the way home as life moves on. And so I go about my work passionately and resolutely; I am driven to do so.

Like a bird following a trajectory with some gravitational or magnetic guidance system – while lacking any clue of what lies at the destination – I forge ahead. I do so trusting that regardless of what, if anything, lies beyond, my adopted cause is worth pursuing. In my case, that ambitious objective consists of trying to get water to where it is needed and keep it away from where it might cause harm, while raising kids who will look out for others and for the planet along their own journeys.

We were recently told again that Jaedin’s heart will not last much longer. He now faces the prospect of a full heart-lung transplant that may be too risky to undertake. We know our time with him may be short; at an unpredictable moment on an unpredictable day that lies somewhere ahead in our unpredictable future, my mobile phone may ring with a call from the transplant centre – I realise that it will be a call that will either end his life or extend his life. That is certainly a nerve-wracking prospect; but in the end, don’t we all face that same risk every day with every one of our relationships? A similar call could come to any of us without any warning whatsoever. Any one of us or our loved ones may be living our last day today – we can’t control that, but we can try our best to make the most of the day: Don’t leave anything unsaid; treat everyone with respect; don’t live with any regrets. Do your best in life, and the best in life will come back to you. It may not come about in the way we hope or expect it to, but one way or another, I am convinced that things will always come around full circle in the end. And each time we find ourselves staring at the sky with a remote sense of familiarity, we also find ourselves one step closer to home than the time before. Whether that destination is back to stardust or to something that lies beyond, let’s make every heartbeat count in the meantime, because every single one is a blessing and a miracle in itself!

So there you have it: If you sign up for one of my classes, you will see what I do.

But this story is about my philosophy and my family: That is why I do what I do.

What’s your why?

If we’re fortunate enough to work together in the future, I would love to discover the answer.

Worlds>>>Collide

About the instructors: Krey Price – Professional Profile